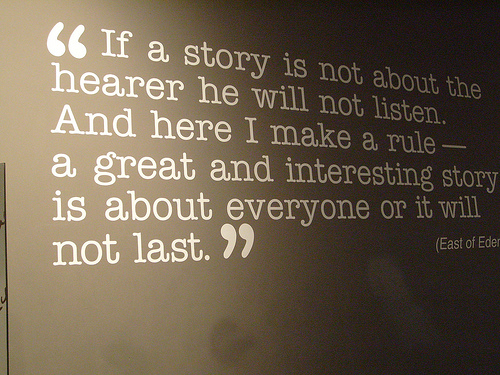

During the process of developing the idea of the Accounts of the Conflict story-telling archive, the question of what constitutes a ‘story’ had to be addressed. The preferred approach of the project team is to be as open and as flexible as possible when it comes to offers of material for deposit in the archive, or in the process of cataloguing publicly available story-telling outputs where deposit is not possible. However, it was still felt necessary to give some consideration to the boundary of story-telling activities so as to avoid unrealistic expectations of what could be achieved.

My colleague, Gráinne Kelly, stated a definition of story-telling projects in the Healing Through Remembering ‘Storytelling Audit’ published in 2005:

The focus of the audit was on projects that allow for telling, reflection, expression, listening and collecting of stories as the primary and core motivation behind their inception and implementation.

Kelly, G. (2005); p.16.

There are, of course, story-telling projects which take a considered decision not to record the stories that are told (or, in some cases, to record the stories but to keep them almost entirely private). Given that Accounts of the Conflict is engaged in establishing an archive of stories it can only, by definition, catalogue and archive stories that have been recorded in some physical / digital format.

For those story-telling projects which have recorded stories, the most straightforward cases are likely to be those which record and reproduce the story with a minimal level of editing or selection. The recording format might be one of the following:

- on (digital) video (audio visual),

- on (digital) audio (audio only),

- or in a written format (long hand or typed).

The recordings might then be made public on DVDs; CDs; CD-Roms; or via a Web site. Beyond the most straightforward story-telling process there are instances where decisions will have to made as to whether or not the ‘story’ should be included in the Accounts archive.

It is true that many people tell their stories outside of a story-telling process. Since 1968 many people have been interviewed by the media and have given a personal account. It has to be recognised that media interviews do not usually allow the interviewee to talk for as long as they wish and then for the interview to be reproduced in its entirety. Even allowing for the fact that a media interview might be the only version of the ‘story’ available, practical considerations mean that these accounts have to be excluded from the archive. Such interviews can be obtained via other routes, such as newspaper libraries or archives of broadcast material (see, for example, Heathwood’s Collection of Television Programmes.

Similarly, many people have told their account in the form of an autobiography or a memoire (outside of a story-telling process). At this stage of the Accounts project it would not be possible to write detailed catalogue entries for all of this work in the archive. However, in order to assist research in this area, a link will be provided to those autobiographies that are referenced in the CAIN Bibliography.

The Accounts team is aware that some of the currently funded Peace III story-telling projects are producing ‘non-typical outputs’. There are at least two ‘story-telling’ projects which are conducting recorded interviews but which will produce, as a final output, a theatrical performance. Such outputs would not be classed as stories because, while they are based on interviews, the final script is a dramatised version. Although dramatised stories will not be included in the Accounts archive, such accounts can be accommodated within a planned section of the CAIN Web site.

The Accounts project anticipates that digital copies of some stories, in the form of textile art work, will be offered to the archive. It is certainly a possibility that other works of art (painting, drawing, sculpture, photograph, etc.) might be offered to represent the artist’s story. The question arises whether or not a photograph of a work of art, on its own, is sufficient to form a story. The main problem is that the works of art could be open to wide interpretation. When the viewer is removed from the underlying story by time, geographic location, culture, language, etc., the more likely it is that the story will be misunderstood or not fully appreciated. The Accounts team feels it would be best if works of art are accompanied by an explanation or interpretation (audio-visual, audio, or written) by the story-teller, or in their absence by a curator who knows the underlying story.

There will be examples of stories that have been produced by individuals who have not taken part in a formal story-telling process. Some people will have written their account of their experiences with a view to them being included in a collection. These individuals will have been aware of the concept of story-telling but will have been motivated by a desire to record their own story (often in written format) without recourse to a formal story-telling project. In the past CAIN has received, without soliciting, some stories which were written unsupervised. Despite the fact that these types of stories have not been produced as part of a formal process, the motivation of the story-teller is likely to be very similar to those who took part in a story-telling project. The Accounts team will include these stories in the archive but will indicate that they were not written as part of a process involving other people.

It is acknowledged that there will always be some divergence of opinion as to what constitutes a story. Nevertheless, the team will endeavour to be as accommodating as possible as it documents story-telling work and accepts personal accounts for deposit in the archive.

- Problems Maintaining Interviewee Anonymity in a Small Region - 21st October 2014

- Defining a ‘Story’ - 11th August 2014

- Preserving & Accessing Stories - 1st May 2014