This post was originally published on the website of the Northern Ireland Foundation on 9 April 2014. The author is Eoin Dignan. Thanks to Eoin and the Northern Ireland Foundation for permission to republish the post here.

INCORE’s EU Peace III-funded ‘Accounts of the Conflict’ project is building a digital archive of personal histories narrating the Northern Ireland conflict. In 2006, Jon Elster distinguished a third phase in transitional justice evolution by its emphasis on transnational learning (1). Accordingly, a core aspect of INCORE’s project is a seminar series delivered by international memory work experts.

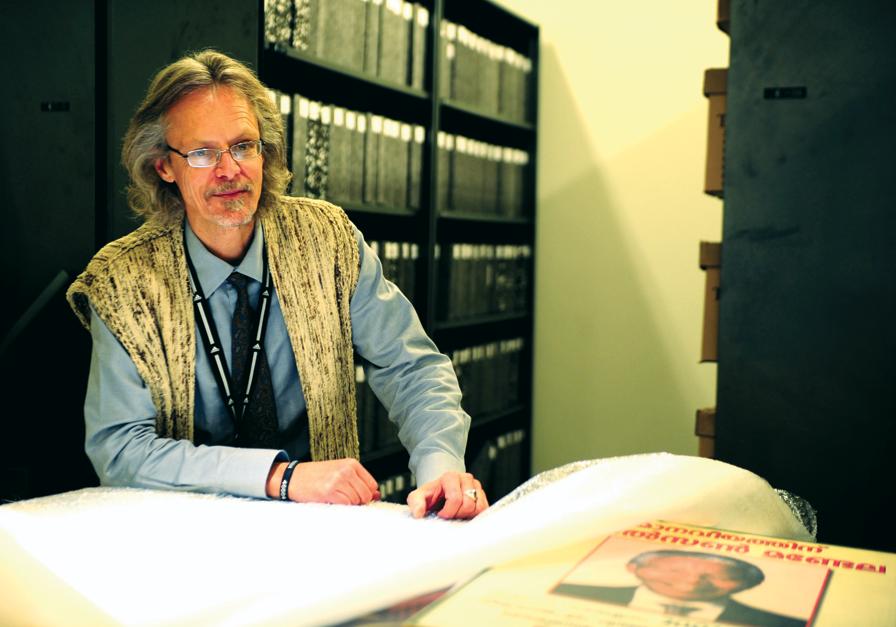

The fourth seminar, ‘Remembering, Forgetting and South Africa’ (video), on 19th March at Skainos, welcomed a particularly notable contributor. Verne Harris is director of Research and Archive at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, and was Mandela’s personal archivist from 2004 to 2013, subsequently lead-editing a best-selling compilation of Mandela’s memoirs entitled Conversations with Myself. As former Deputy Director of the National Archive, he was their liaison with South Africa’s landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). As the most influential of such bodies, the TRC model has been replicated in numerous transitional justice contexts.

Harris reflected upon the legacy of state memory work with disheartened candour, cast scorn on opaque archival structures emerging in South Africa, and outlined the ‘lessons we should have learnt’ in the almost 20 years since post-apartheid memory work began in earnest. His review provided a cautionary tale to other memory projects, and was oriented around issues considered significant in a Northern Irish context.

Harris’ overview was topical, owing to South Africa’s proposed introduction of dogmatic secrecy laws, in violation of the tenets and innovations of the TRC: transparency and accountability. Yet it coincides with our accelerating domestic debate around the flags issue and the possible formation of a Truth Commission body as proposed by Dr. Haas and championed by Labour.

Awash in memory … we know so little

Harris set out the strategy adopted by Mandela’s transitional post-apartheid democracy, in its efforts to distinguish democratic South Africa from the enmities and injustices of its ‘pasts’. He encapsulated Mandela’s ethos as: ‘to find a liberatory forgetting, we would first have to do the difficult remembering’, adding that memory work ‘is important because it gives us the promise of a liberatory future … it is not about the past, it is about the future.’

This kick-started one of the most ambitious state memory projects ever conducted, encompassing ‘state historiography, numerous state-funded oral history projects, new curricula for schools, museums, new archives … we’ve been awash in memory’. The TRC became the most innovative and high-profile consequence of democratic South Africa. By binding truth to conditionality of amnesty, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission represented unprecedented ambition in its evolved conception of truth as the mechanism for delivering justice (2).

The TRC’s judicial model was democratic, transparent, public and unique. The process sought to pre-empt accusations of impartiality by acknowledging ANC culpability in human rights violations. Representatives of the independent commission were publically nominated and the process, endorsed by Parliamentary Act, emphasised transparency. Hearings were in public.

The determination to provide legal accountability, against the ‘crass impunity’ and ‘partial justice’ that affected victim support for the blanket-amnesty Argentinean (1983-84) and Chilean (1990-91) Truth Commissions, resulted in a conditionality of amnesty (3) that Mr. Harris acknowledges as ‘remarkable’. Amnesty was individualised; perpetrators of gross violations could apply within a 16-month window, exchanging full disclosure for criminal and civil court reprieve dependent on fulfilling qualifying criteria.

Yet Harris’s concise, considered lecture was suffused with frustration. ‘We know so little about the past, so many voices are still disavowed … there are so many secrets, so many lies, only a handful of people have been punished for their crimes. Relatively few have found healing and we remain a profoundly damaged society.’

And so Harris’ uniquely intimate critiques posed the question, ‘Why? After so much memory work?’

Shadows of failure

Between 1990 and 1994, Nelson Mandela steered South Africa’s formal transition to democracy through a three-pronged ‘strategy for reckoning with the past’. A new flag, anthem and eleven recognised languages were early changes. Their ‘traction hinged on the other two prongs’. Mandela implemented provisions for reparation and empowerment and announced a restructuring of the economy and a redistribution of ‘wealth, skills and opportunity’.

According to Harris, South Africa has failed on each account. ‘That kind of nation-building’ – of flags and anthems – almost always casts a xenophobic shadow, providing an intriguing if unarticulated overlap with Dr. Haas’ proposals for a new Northern Irish flag. He elaborates South Africa’s ‘deep suspicion of foreigners’ and ‘inversion of apartheid logic’ directed against darker North Africans.

While some economic empowerment schemes have been ‘reasonably successful’, they have been too slow to bring change, particularly land redistribution. As a result, large segments of the population are ‘carrying rage’. Economic restructuring has not worked, leaving South Africa more unequal than in 1994, now ‘the most unequal society on earth’.

Parallel challenges

In January, Skainos was the scene of rioting, sparked by the Listening to Your Enemies festival, which invited Brighton Bomber Patrick Magee to meet Jo Berry, whose father died in the explosion.

As Harris relayed six fundamental lessons South Africa ‘should have learnt’, he drew parallels between the challenges facing Northern Ireland’s memory work and South Africa’s: ‘Like my country, yours is very beautiful, hospitable but also fundamentally damaged by its pasts … you can see it physically … you can see the imprint of the past.’

Lessons to be learnt

Harris describes the persistent ‘myth’ that 22,000 victims ‘came to the Truth Commissions, told their stories, their experiences were affirmed, and they found healing.’ The first lesson is never to take this for granted; the majority of victims did not find healing. Setting a timeframe, rather than ‘creating a continuing space for storytelling’ just opens the wound. ‘Every time a story is told it changes, things which couldn’t be talked about five years ago can now be perhaps named, and in another five years we can then perhaps start to go into the really difficult spaces.’

Harris’ second point: rather than overemphasising individual experiences, narratives must evolve through community discourses. This is a common critique, made elsewhere by Mahmood Mamdani, who states ‘the Commission’s analysis reduced apartheid from a relationship between the state and entire communities to one between the state and individuals.’ Harris wishes to ‘connect a network of stories and to build within communities ownership of those painful pasts.’

Harris cites the story of the Worcester bombings. One of the perpetrators sought an opportunity to apologise to the affected community. This process evolved independently. The community took ownership for developing this reconciliation and nurturing offshoot histories and narratives. This was a civil society mechanism, not a state-centred project: ‘We need more of these projects.’

Thirdly, there can be no single past, no one-track narrative. Effort must be made to bring ‘hostile voices into conversation, dominant voices … with less empowered voices’. Within the TRC context, stories could not emerge fruitfully. With a sigh, Harris admitted there remain certain truths that South Africa is unwilling to acknowledge — noting that the majority of police officers prior to independence were black. A rigid prevailing national narrative within schools also obstructs exploration of cathartic personal experiences. Othershave elaborated on an underrepresentation of female and illiterate ‘truths’ as evidence of exclusionary truths dictated by ‘dominant voices’ (4).

Fourthly, ‘like many countries’ South Africa adopted ‘easy labels … victim, perpetrator, beneficiary, survivor’, but ‘it is when we foster that complexity and honour that space that memory work begins to enable liberatory futures’.

Harris asserts the importance of reaching youth who are exhausted with the past, impatient and ‘uncomfortable with celebratory accounts of the glorious struggle against oppression’. Rather than spoon-feeding a state narrative, what truths would liberate this generation, and how best to harness the lessons they can teach?

Ghosts in the machine

Harris’ forceful final lesson asserted the need for accountability, paraphrasing Derrida: ‘No justice seems possible or thinkable without the principle of some responsibility, before the ghosts of the dead (be they victims of war, political or other kinds of violence), before the ghosts of the living (who are damaged by violence past and present) and before the ghosts of those who are not yet born.’

The TRC’s time-window forced the hand of prospective applicants; 7,116 applied, among whom 1,973 received a hearing and were confronted by their victims before the Commission; 1,167 amnesties were granted (5). But the TRC meted flawed justice, addressing a fraction of documented murders (6).

Since the closing of this window, there have only been two prosecutions and there is ‘no evidence that there will be systematic prosecution’. These inadequacies are so significant that Harris denounces what became ‘effectively a blanket amnesty … we’re paying a terrible price for that, in terms of a culture of impunity’.

He does not claim to have a solution for the complications of transitional justice, but he considers it essential that those in power today acknowledge their complicity. Speculatively, Harris pondered a Cambodian approach based around symbolic trials, rather than risking mass disillusionment after unfulfilled judicial promise.

Concluding impressions

A lengthy opportunity for post-lecture questions crystallised central themes and personal impressions.

Harris emphasised South Africa’s glaring inability to sustain cultures of accountability and transparency. He highlighted his foundation’s current difficulties accessing public records and the struggle against secrecy acts, noting that ‘you need a lot of money to force records into public domain’, before querying Northern Ireland’s situation regarding sensitive records.

Tragically, South Africa’s state-managed memory work, once so ambitious, has dissipated. Asked whether the ‘state has closed the door’ post-Mandela, Harris described the changed climate confronting institutions and foundations ‘under huge pressure in terms of funding … the environment is changing quickly, their existence is under threat’.

The process has failed to disperse ownership of memories; tried individuals rather than institutions, opted for ‘easy labels’; did not build community projects and ultimately ignored the ‘really difficult spaces’. To Harris, memory work requires long-term, grassroots solutions. Yet, in his view South Africa’s state-centred approach has stifled individual and community initiatives — ‘people are waiting for the state, for funders, for experts from outside’ and this has not fostered a space open to contested pasts, fundamental to building reconciliatory dialogues and attaching more complex, empathetic identities to the ‘other’. What’s more, stagnant narratives lack space to evolve and address concerns relevant to the post-apartheid generation. Such concerns are likely a legacy of failed structural reforms.

I was thus reminded of former TRC member Yasmin Sooka’s 2006 appraisal, which stressed inadequate structural reform and the new inequalities and impunities it reproduced (7). In what Elizabeth Stanley termed ‘double victimisation’ (8), the absence of proposed reparation payments and structural reforms has dovetailed with the de facto blanket amnesty and a judicial mandate that excluded structural violence (9). Consequent embitterment can damage trust and further inhibit the emergence of community-led reconciliation.

As INCORE prepares to launch Northern Ireland’s online storytelling space this autumn, Harris provides timely insights. Two further seminars in the ‘Accounts of the Conflict’ series will lend further guidance. Next up: Liz Silkes, discussing ‘Archive Development and Civic Engagement at Sites of Conscience’ on 16th April at the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, Titanic Quarter.

NOTES

(1) Elster, Retribution and Reparation in the Transition to Democracy, pp. 325-326.

(2) Elizabeth Stanley, ‘Evaluating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’, Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 39, No.3 (2001), p. 525.

(3) Boraine, ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. Amnesty: The Price of Peace’, pp. 299-316.

(4) Jeremy Sarkin, ‘An Evaluation of the South African Amnesty Process’, in A. R. Chapman and H. van der Merwe (Eds.), Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: Did the TRC Deliver?, pp. 93-115.

(5) Sarkin, op. cit., p. 94.

(6) Stanley, op. cit., p. 527.

(7) Yasmin Sooka, ‘Dealing with the past and transitional justice: building peace through accountability’,International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 88, No. 862 (2006), p. 324.

(8) Stanley, op. cit., p. 539.

(9) Elster, op. cit., p. 8.

- Reconciliation Lessons: Verne Harris On South Africa - 17th April 2014